Simon Bevan

Cranfield University

4th May, 2020

In the current environment where many university library buildings across the world are closed due to the Covid-19 pandemic, print versions of material, particularly in libraries, are simply not available to students. So how will this situation affect our thoughts on the types of materials university libraries will provide for students and faculty in the future?

Every piece of research on the effectiveness or user preference for print or electronic is at best a snapshot as the literature ages and technology develops. A meta-analysis of this literature published in Scientific American in 2013 reported that there had been over 100 studies since the 1980’s. Through these studies, we have seen that as technology improves to host digital reading materials, attitudes towards reading on paper versus screen have changed. “Before 1992 most studies concluded that people read slower, less accurately and less comprehensively on screens than on paper” [i]. While many of the post ’92 studies still support these findings, an almost equal number have found that reading on screen is just as effective as reading a print version.

Showing a similar transition in reader proficiency, a more recent study by Kong et al (2018)[ii] found that reading on paper was better than reading on screen in terms of comprehension but this difference diminished between studies before and after 2013.

So, what might be the expectations of future generations of learners? And how can academics reflect different learning expectations and needs to provide effective resources?

Length of text

The length of the text seems to be a critical factor. If the text is long and needs to be read carefully then studies show that many students still often prefer a printed book. This is the case even if the item is available as an e-book with options for making notes, full-text searching and digital highlighting. This is not the case when it comes to shorter texts.

Multitasking

Perhaps it’s nothing to do with the format per se but with device functionality. A book does one thing, whereas, a device with connectivity has a myriad of uses that are almost designed to try and attract the user away from what they’re actually doing. For example, a 2017 study[iii] found that in the US 85% of students report multitasking while reading online compared with only 26% of those reading print material. Another study[iv] stated that in only a 15-minute period, students switched tasks an average of 3 times when they read electronically.

Matching the way of reading to the task

Naomi Baron (2016) talked about the “growing trend for universities to adapt their curricula to fit the proverbial “procrustean” bed of a digital world – a world tailor-made for skimming, scanning and using the “find” function rather than reading slowly and thoughtfully.” [v] She suggests university teachers are discarding long or complex reading assignments in favour of short (or more straightforward) ones, condensed versions of texts and shorter bite-sized reading material, which may well impact on comprehension. Perhaps the question then, is how can universities help students read text thoughtfully, reflectively, and without distraction on digital devices?

When preparing classes, perhaps teachers not only need to consider factors affecting how their students are learning, for example, online or at a distance, but also what they want students to learn in the session and therefore whether print or digital format is more appropriate. Wolf’s best hope for our reading future is the ‘bi-literate’ brain[vi] – one that uses the optimal skills of each reading style so that students can read deeply as well online as in print – something for faculty to consider. What should teachers be recommending to their students?

A dual approach

Perhaps the question is not either/or print or electronic but both? A Dartmouth study [vii] found that electronic reading helps a reader remember the concrete facts, but not the abstract concepts. To learn and remember abstract concepts, paper reading is more effective. The recommendation was for students to read in both electronic and paper forms as both types of readings serve different purposes but each has their own benefits. This may be the advice as an ideal but in the real world, students simply don’t have the time to read the same thing twice in different formats. This implies a tension between reading for the purposes of retention or reading more widely to acquire a wider breadth of knowledge.

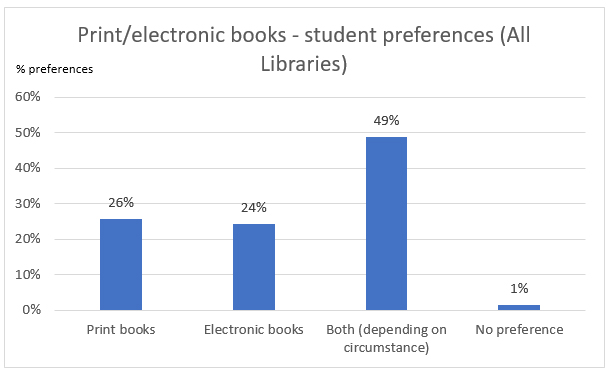

At Cranfield University, a wholly postgraduate University in the UK, students were asked in a study in 2020, whether they had a preference for print books, electronic books, both depending on circumstance or no preference. The overall picture showed that, of the 355 respondents, almost an equal number preferred either print (26%) or electronic (24%) but the majority (almost half), were happy with either depending on the circumstance. So, what are those circumstances?

Figure 1. Student preferences for print or electronic books

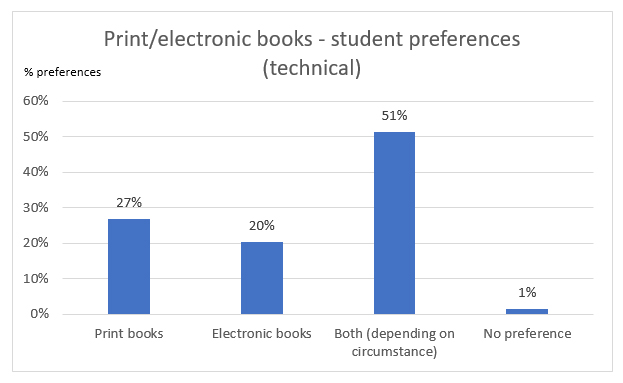

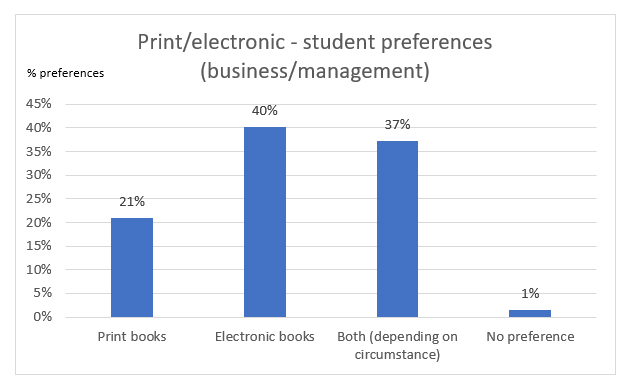

We have three libraries at the University, two largely technical (serving three Schools: Aerospace, Transport & Manufacturing; Water, Energy & Environment; and Cranfield Defence & Security) and a third Library embedded within the School of Management. If the results are divided between technical and business/management, then they show a slightly different picture.

Figure 2. Student preferences for print or electronic books (science and technology)

Figure 3. Student preferences for print or electronic books (business and management)

For the technical schools, students appear to have a preference for print over electronic, but over half are happy with both depending on circumstance. For students who use the Library within the Management School, their preference is clearly for ebooks. Why might this be the case?

It may be related to subject or to proportions of part-time off-campus respondents, or perhaps more likely to the length of time required to read a book – the propensity for MBA’s to be provided with specific readings and shorter articles or reports which are more conducive to electronic access. This snapshot of preferences demonstrated that there could be a selection of variables as to why a student would choose one particular way of reading a resource over another. Follow up focus groups in this area would be useful in the next academic year to provide further insight of preferences.

Although there are a few exceptions (eg, Florida State Polytechnic University and Nevada State College which offer an entirely electronic library service), most HE Libraries now provide a mixed offering to their customers of both print and electronic books. From the point of view of a Library providing the best possible service to students there are considerable advantages to providing more electronic texts: books are available 24/7, generally accessible from anywhere in the world and they are easily adapted using screen reading software for those with reading disabilities. Students place considerable value on their ability to work within the Library, and the reduction in print versions of books allows libraries to more flexibly adapt the space to student requirements for different styles of study (by withdrawing physical stock and removing fixed shelving). This benefit is less relevant for those studying online or at a distance, but the increase in e-book provision provides enhanced access for all those not able to come into the Library, as we are experiencing during the current COVID-19 pandemic. However, when libraries are open, as well as a quiet environment conducive to study, one reason why students do like to work in the Library is the easy availability of physical stock.

Similarly, from the point of view of the Library providing a high quality service to all, there are also disadvantages of using electronic books including the number of different publisher and intermediary interfaces with which students may need to become familiar with. Other drawbacks are access and authentication issues, finding relevant material, licencing and digital rights issues, shortcomings in functionality of the different interfaces, and not least the cost – electronic books bought or subscribed to by an academic library tend to be considerably more expensive than print versions.

To some extent the research shows that the move from reading books in print to ‘e’ is in an evolutionary phase. Considerable changes have occurred in ebook platform functionality over the last 10 years and there are likely to be further developments in future, which may perhaps make ebooks better aligned to new pedagogies, for example, providing more complex non-linear structures to facilitate more adaptive learning. This is something that traditional textbook publishers are investing in heavily – for example, McGraw-Hill now consider themselves ‘a learning science company’[viii] and Pearson are phasing out print textbooks.

As this article highlights, a number of factors affect the choices made between using print or electronic books. These include, text length, the student’s attention span and their desire to continue to multi-task on an electronic device during their academic reading, and teaching staff beginning to more closely match the task with the most appropriate format of reading material. The likelihood is that a dual approach will continue partly based on an academic understanding of reading effectiveness, but also partly based on personal preference. Where there is demand for both formats, and evidence shows that both formats are addressing a different learning need, Libraries should continue to provide both formats.

Simon Bevan

Simon Bevan, University Librarian at Cranfield University, contributes expertise to the Centre for Innovation in Learning and Education (CILE). The joint virtual centre aims to develop new knowledge in innovative education, business-engaged educational design and innovative delivery modes in undergraduate provision within UK Higher Education. Through joint research, the sharing of best practice and the design of innovative education pathways, Aston and Cranfield Universities are supporting the proposed development of a new model STEM-focused university in Milton Keynes.

This blog has been produced for the Centre for Innovation and

Learning in Education, a Catalyst OfS funded project.

[i] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/reading-paper-screens/

[ii] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.005.

[iii] https://www.fosi.org/good-digital-parenting/electronic-vs-print-reading-which-better/

[iv] L. D. Rosen, K. Whaling, L. M. Carrier, N. A. Cheever, and J. Rokkum, “The Media and Technology Usage and Attitudes Scale: An empirical investigation,” Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 29, No. 6 (2013): 2501–2511.

[v] https://newrepublic.com/article/135326/digital-reading-no-substitute-print

[vi] https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/notetoself/episodes/reading-screens-messing-your-brain-so-train-it-be-bi-literate

[viii] http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/technology/2015/10/adaptive_learning_software_is_replacing_textbooks_and_upending_american.html

Simon

This is a very very interesting insightful piece. It has come just at the right time. Lots of good data to

Thanks Helen, it seems to be a continuously evolving debate!

Many factors at play here which I imagine we HE librarians all recognise! From a more cynical mindset (triggered by your mention of Pearson) there is another reason for publishers to favour e-books over print: digital rights management. Publishers can prevent there being any second-hand market in their e-books (which they can’t in print); they can refuse to sell certain titles as e-books to libraries at all and only sell them to individual students (which they can’t legally do with print) and they can restrict the number of times a Library e-book is borrowed per year (which, again, they can’t do with print). E-books therefore provide them with a number of additional ways to exploit their effective monopoly position for any given title.

Hi Hazel,

Many thanks for your comments. Yes, agreed, ebooks certainly give publishers more of an ability to limit circulation to libraries/institutions/regions. Given that there isn’t much money for the author in monograph publication, perhaps more should consider publishing open access… but that’s another topic altogether!

Very interesting read. I am a little surprised that the business students seem to embrace ebooks – I have not found it to be the case to be honest!

It would be interesting to know which ebook platform Cranfield are using – is it the same platform for technical and business?

Hi Dawn,

Many thanks for your comments. Yes, we were a little surprised as well (although the finding was mirrored by another institution). I suspect it may have something to do with Faculty staff referring students to specific parts of the text rather than to the whole book, although we didn’t collect any evidence of this. We have a range of platforms for ebooks across the university but again, it would be interesting to look into this further.